For many PhD applicants, the first email to a potential supervisor feels deceptively simple. It is often treated as a short introduction or a polite expression of interest. In reality, this email functions as an academic gatekeeping document. Supervisors use it to assess whether a student understands research culture, has done intellectual groundwork, and is capable of formulating a viable doctoral trajectory. A poorly written first email rarely receives feedback; it is simply ignored.

This article explains how to write the first email to a professor for a PhD application in a way that aligns with academic norms, supervisor expectations, and doctoral selection logic. Rather than offering a generic template, it breaks down why each component of the email exists, how it is evaluated implicitly, and what typically goes wrong when applicants misunderstand its purpose. The aim is to help you write an email that signals research readiness rather than desperation.

Why the first PhD email is an academic screening tool, not a courtesy message

From a supervisor’s perspective, the first email is not about politeness or enthusiasm. It is a filtering mechanism. Faculty members receive dozens—sometimes hundreds—of unsolicited PhD enquiries each year. Most are immediately recognisable as mass-sent messages that demonstrate no engagement with the supervisor’s work. These emails are not rejected because the students are weak, but because the emails fail to demonstrate academic fit.

Academically, supervision is a long-term intellectual commitment. A supervisor must judge whether your interests align with their expertise, whether your research direction is plausible, and whether you understand the norms of doctoral study. The first email therefore substitutes for an initial research conversation. If it does not demonstrate preparation, specificity, and clarity, the supervisor has no incentive to respond.

Supervisors are not evaluating your personality in the first email; they are evaluating your academic signal-to-noise ratio.

What supervisors implicitly assess when reading your first email

Although supervisors rarely articulate their criteria, the first email is read through a set of implicit academic questions. These include: Has the applicant read my work? Do they understand what I actually research? Is their proposed direction realistic at doctoral level? Are they asking for supervision, funding advice, or general information—and are they clear about that request?

Crucially, supervisors are also assessing academic independence. A strong first email shows that the applicant has already engaged with the literature, identified a tentative research problem, and understands how their interests intersect with existing work. A weak email signals dependency, vagueness, or misunderstanding of what a PhD entails. These signals matter because doctoral supervision is not taught coursework; it is guided independent research.

Doing your homework: research preparation before writing the email

Before writing a single sentence, you must complete a minimum level of academic preparation. This includes reading several of the supervisor’s recent publications, understanding their methodological preferences, and identifying how your interests connect to their work. This step exists because doctoral supervision is topic-specific. Expressing interest without demonstrating familiarity suggests you have not yet entered research mode.

You should also review the department’s doctoral focus areas and the university’s PhD structure. This allows you to situate your enquiry accurately. If you are unsure how to assess whether your background and interests are academically aligned with doctoral expectations, the guidance in Research Paper Structure and Format helps clarify what constitutes research-level thinking.

Avoiding the “spam letter” problem in PhD enquiries

The most common reason PhD enquiry emails fail is that they read like spam. These emails are generic, interchangeable, and could be sent to hundreds of professors without modification. They often begin with “Dear Professor” and include statements such as “I am very interested in your research” without specifying what that research actually is.

Academically, such emails fail because they do not establish research fit. Supervisors assume—correctly—that the sender has not engaged with their work. Even highly qualified applicants are filtered out at this stage. To avoid this, your email must include specific references to the supervisor’s research themes, publications, or methodological approaches, integrated naturally rather than listed mechanically.

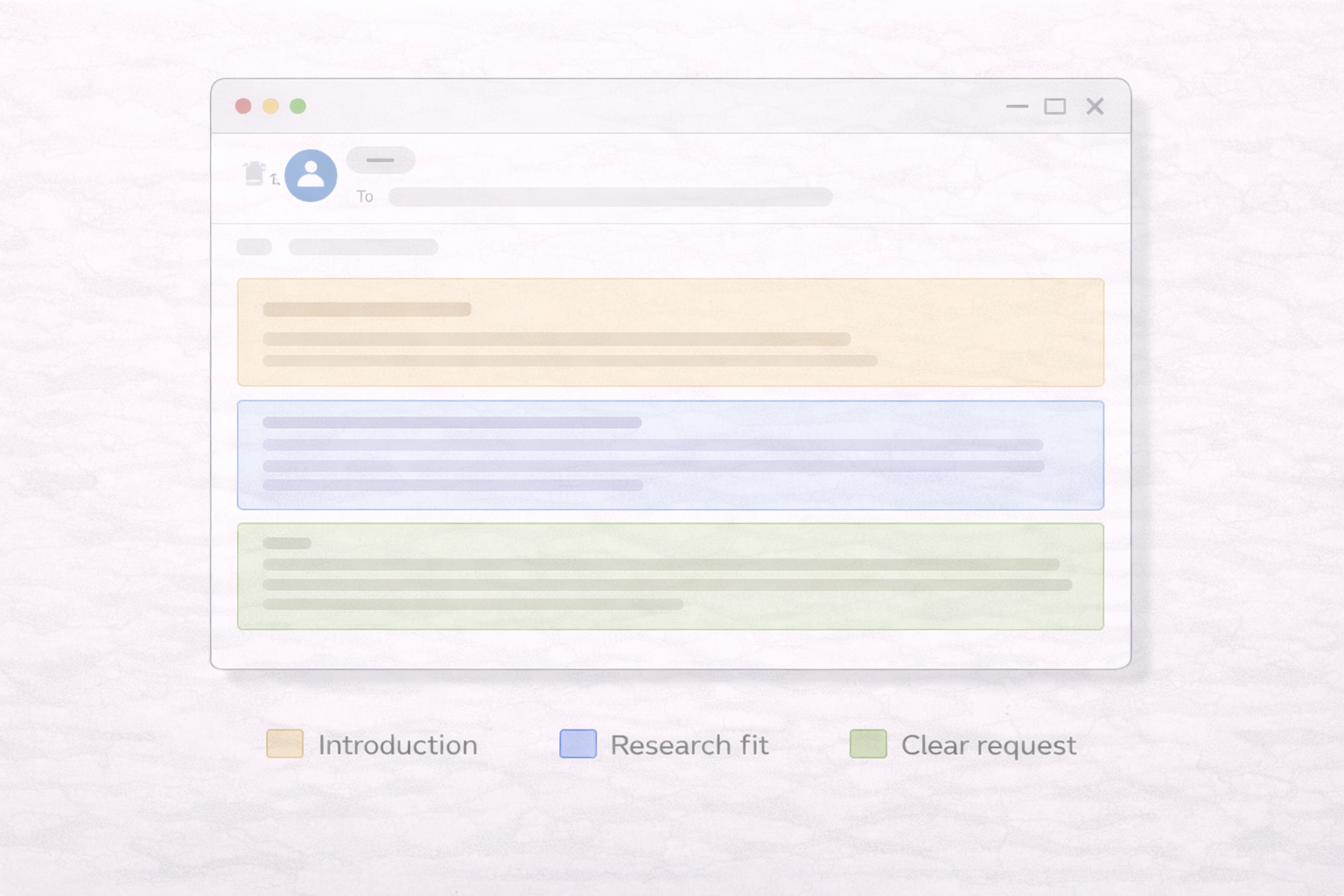

Structuring the first email: academic logic, not length

An effective first email to a PhD supervisor is usually concise, but it is also densely informative. Length is not the primary concern; clarity and relevance are. The structure should follow academic logic: identification, contextualisation, alignment, and request. Each paragraph must perform a clear function and contribute to the supervisor’s ability to assess fit.

Unlike casual emails, this message should not meander or rely on vague enthusiasm. Every sentence should justify why the supervisor should invest time in responding. If you struggle with structuring academic communication clearly, reviewing Essay Structure Explained for University Students can help you think in terms of purpose-driven paragraphs.

Opening paragraph: identifying yourself with academic precision

The opening paragraph should establish who you are academically, not personally. This includes your current or most recent degree, your discipline, and—where relevant—your institutional context. The aim is to allow the supervisor to immediately place you within an academic trajectory.

For example, stating your degree without explaining its relevance to doctoral research is insufficient. The opening should subtly indicate progression: how your background prepares you for research, rather than simply listing credentials. Overly informal greetings or personal anecdotes undermine the academic tone expected at this level.

Demonstrating research fit through specificity

The core of the email is the demonstration of research fit. This is where many applicants fail by being either too vague or too ambitious. You are not expected to present a finished proposal, but you must articulate a focused research interest that intersects clearly with the supervisor’s expertise.

This is best achieved by referencing one or two specific aspects of the supervisor’s work and explaining how they inform your developing research interests. The explanation should be analytical, not flattering. Statements such as “Your work inspired me” are far weaker than explanations of how a particular concept, method, or finding shapes your proposed direction.

Stating your request clearly and academically

One of the most damaging mistakes in first PhD emails is failing to state what you are actually asking for. Supervisors should not have to infer whether you are seeking supervision, advice, or general information. Ambiguity signals uncertainty about the PhD process.

Academically appropriate requests are explicit but modest. For example, requesting a brief discussion about potential supervision is reasonable; asking for guaranteed supervision or funding is not. Clarity here demonstrates procedural literacy, which supervisors value highly.

Do not hide your request behind vague interest statements. Academic clarity is a sign of doctoral readiness.

Addressing funding without undermining academic seriousness

Funding is a legitimate concern, but it must be raised carefully. The first email should not read like a funding enquiry disguised as a research interest. Instead, funding should be framed as a procedural step that follows academic alignment.

A brief, neutral sentence indicating that you intend to apply for scholarships once supervision is confirmed is sufficient. This reassures the supervisor that you understand the process without shifting focus away from research fit.

What not to include in the first email

Many applicants overload the first email with attachments, personal stories, or exhaustive detail. This is counterproductive. At this stage, supervisors are assessing alignment and seriousness, not conducting a full evaluation. Overloading the email creates cognitive friction and suggests poor academic judgement.

Unless explicitly requested, do not attach full proposals, transcripts, or certificates. These materials can be offered later if the supervisor expresses interest. The first email should remain a focused academic introduction, not an application dossier.

Common mistakes that lead to silent rejection

Silent rejection is the norm, not the exception, in PhD enquiries. Understanding why emails fail helps you avoid misinterpreting non-response as a reflection of your ability. The most common failures include generic language, lack of supervisor-specific detail, unclear requests, and an overly informal or deferential tone.

Another frequent issue is misalignment between the applicant’s interests and the supervisor’s actual research area. Even well-written emails are ignored when the fit is weak. This reinforces why preparatory research is non-negotiable.

| Common mistake | How supervisors interpret it |

|---|---|

| Generic greeting and vague interest | Mass email with no genuine research engagement |

| Unclear or hidden request | Lack of understanding of PhD processes |

| Overly long autobiographical detail | Poor academic judgement and focus |

| No reference to supervisor’s work | No evidence of research preparation |

The table illustrates that most failures are procedural rather than intellectual. Strong candidates are often filtered out because their email does not communicate readiness in an academically recognisable way.

After sending the email: academic patience and follow-up etiquette

Once the email is sent, restraint is essential. Supervisors are under no obligation to respond, and immediate follow-ups are rarely appropriate. If you receive no response after two to three weeks, a single polite follow-up may be acceptable, provided it adds value rather than pressure.

At this stage, rejection or silence should not be personalised. Academic recruitment operates on structural constraints, not individual worth. If you are applying broadly, ensure each email is tailored and maintains the same academic standard.

Turning interest into supervision: the bigger academic picture

The first email is only the beginning of the doctoral application process. Its role is to open a channel for academic dialogue. If successful, the next steps may include sharing a proposal, discussing funding pathways, or refining research scope. Each step builds on the academic signals you establish in this initial message.

If you are uncertain whether your research interests are sufficiently developed for doctoral-level discussion, working through structured preparation—such as proposal planning or research design support—can significantly improve your outcomes. Resources like Proposals and Coursework provide guidance on transforming interests into academically viable research directions.

Writing the first PhD email as an academic act

Writing the first email to a professor for a PhD application is not a networking exercise; it is an academic act. It requires research literacy, clarity of purpose, and respect for scholarly norms. When written well, it signals that you are ready to participate in research culture rather than merely consume it.

Approach the email as you would a short academic text: with purpose, structure, and evidence of engagement. Doing so does not guarantee a response, but it ensures that silence is never due to avoidable mistakes. In doctoral applications, this level of discipline is not optional—it is expected.

Comments