One of the most consequential decisions in academic research is whether to adopt a quantitative or qualitative approach. This choice shapes how research questions are framed, how evidence is generated, and how findings are evaluated by markers, supervisors, and examiners. Despite its importance, many students treat this decision superficially, relying on oversimplified definitions rather than methodological reasoning.

In university assessment contexts, especially at undergraduate dissertation, master’s thesis, and PhD levels, examiners do not assess methods in isolation. They evaluate how well a chosen approach aligns with the research problem, theoretical framework, and claims being made. This article provides a rigorous comparison of quantitative and qualitative research to support defensible, academically sound methodological decisions.

Why quantitative and qualitative research exist as distinct traditions

Quantitative and qualitative research emerged from different philosophical traditions within the social and natural sciences. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist and post-positivist paradigms that assume reality can be measured, modelled, and explained through variables and causal relationships. Its purpose is not merely to collect numbers but to test hypotheses and establish patterns that extend beyond individual cases.

Qualitative research, by contrast, is grounded in interpretivist and constructivist paradigms. It assumes that social reality is complex, context-dependent, and often inaccessible through numerical abstraction alone. Rather than seeking generalisation, qualitative research prioritises depth, meaning, and understanding how phenomena are experienced and interpreted by individuals or groups.

Purpose and research questions in academic assessment

The primary distinction between quantitative and qualitative research lies in purpose. Quantitative studies are designed to examine relationships, test theories, and establish cause-and-effect patterns. Examiners expect research questions that are precise, measurable, and operationalisable, often using language such as “to what extent,” “what is the relationship,” or “does X predict Y.”

Qualitative research questions, on the other hand, are exploratory and open-ended. They aim to understand processes, meanings, and experiences rather than measure variables. Questions typically begin with “how,” “why,” or “in what ways,” signalling an interpretive intent. In assessment, misalignment between question type and method is one of the most common reasons for lower marks.

Research design: fixed versus flexible structures

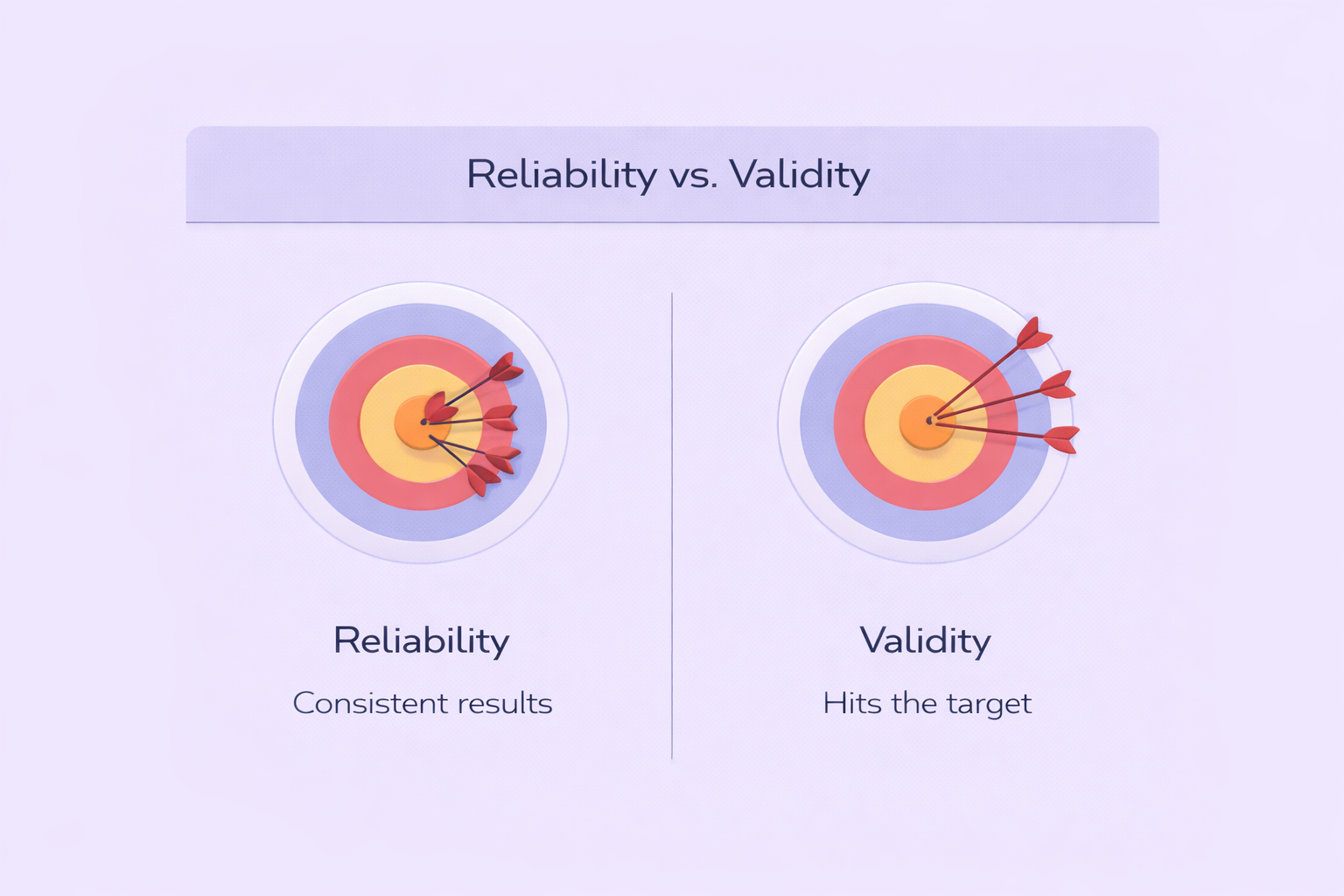

Quantitative research designs are developed prior to data collection and remain largely fixed throughout the study. This includes predefined variables, instruments, sampling strategies, and analytical techniques. Such rigidity is not a limitation but a requirement for reliability and replicability, both of which are central evaluation criteria in quantitative work.

Qualitative research designs are intentionally flexible and adaptive. Data collection and analysis often occur concurrently, allowing emerging insights to shape subsequent inquiry. Examiners assess whether this flexibility is methodologically justified rather than viewing it as lack of planning. Problems arise when students adopt qualitative designs but attempt to impose quantitative expectations of standardisation.

Approach to theory: deductive versus inductive reasoning

Quantitative research typically employs deductive reasoning, beginning with theory, deriving hypotheses, and testing them against empirical data. Academic assessors expect clear theoretical grounding and explicit links between theory, variables, and analytical models. Weak theory integration is a frequent criticism in quantitatively oriented dissertations.

Qualitative research often relies on inductive or abductive reasoning. Rather than testing predefined theories, it may generate or refine theory through engagement with data. Examiners look for reflexivity and conceptual sensitivity, assessing whether theoretical insights genuinely emerge from systematic analysis rather than anecdotal interpretation.

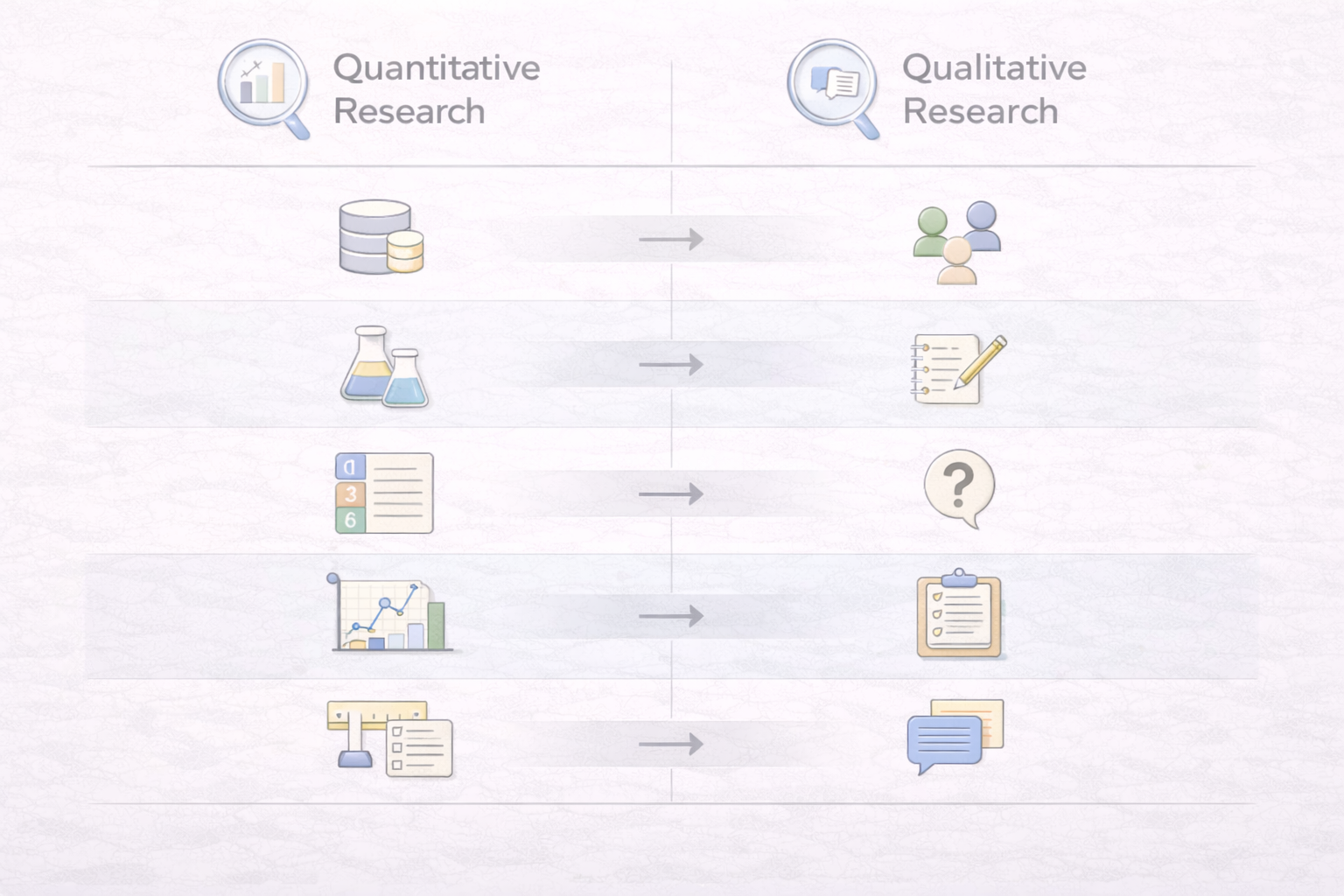

Data collection tools and the role of the researcher

In quantitative research, data collection tools such as surveys, tests, and structured observations are preselected and standardised. The researcher’s role is to minimise influence on data generation, ensuring objectivity and consistency. Assessment focuses on instrument validity, reliability, and appropriateness.

In qualitative research, the researcher is the primary instrument of data collection. Interviews, focus groups, and observations rely heavily on researcher judgment and interaction. Examiners therefore assess reflexivity, transparency, and ethical awareness, recognising that subjectivity is managed rather than eliminated.

Sampling logic and implications for academic claims

Quantitative research typically employs large samples to support statistical inference and generalisability. Examiners expect sampling strategies that justify representativeness and statistical power. Overgeneralisation from inadequate samples is a common assessment flaw.

Qualitative research uses smaller, purposive samples selected for their relevance rather than representativeness. Claims are contextual rather than universal. Problems arise when students make broad generalisations from qualitative findings without methodological justification.

Analytical strategies and evidence standards

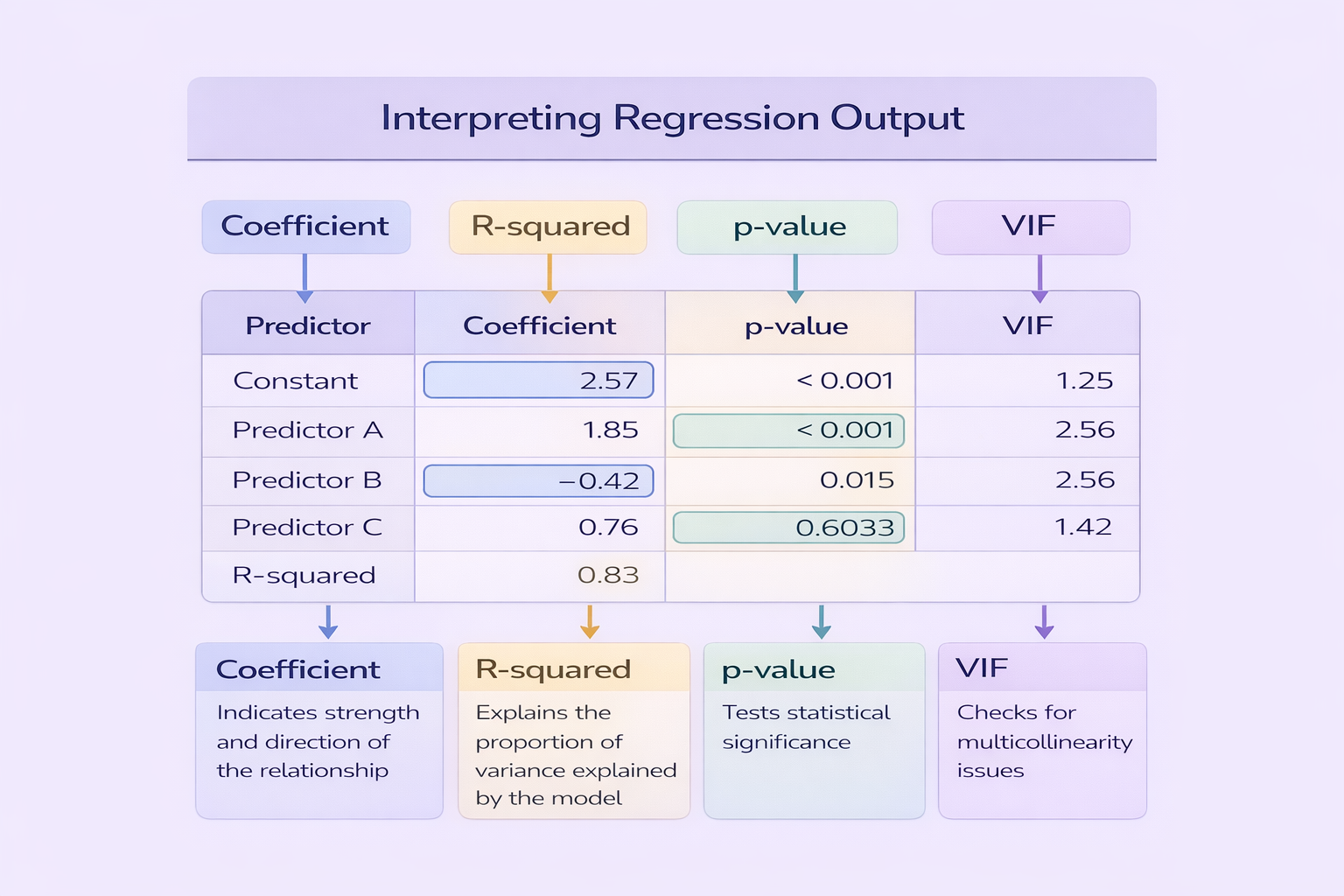

Quantitative analysis relies on statistical techniques to identify patterns, relationships, and effects. Examiners assess whether analytical methods are appropriate, correctly applied, and clearly explained. Misinterpretation of statistics or inadequate justification of tests often leads to critical examiner comments.

Qualitative analysis involves coding, categorisation, and interpretive synthesis. Evidence is presented through themes, narratives, and illustrative excerpts. Examiners look for systematic analysis rather than selective quotation, evaluating whether interpretations are grounded in data.

| Dimension | Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research |

|---|---|---|

| Primary purpose | To test relationships, hypotheses, and causal effects using measurable variables | To explore phenomena in depth and understand meanings and experiences |

| Research design | Structured and fixed prior to data collection | Flexible and adaptive throughout the research process |

| Role of theory | Theory guides hypothesis formulation and testing | Theory may emerge from or be refined through data analysis |

| Data and analysis | Numerical data analysed using statistical techniques | Textual or visual data analysed through interpretation and thematic analysis |

What typically goes wrong in student research

One of the most frequent academic errors is treating quantitative and qualitative research as interchangeable labels rather than coherent methodological systems. Students often select a method based on convenience rather than epistemological fit, leading to weak alignment between questions, data, and analysis.

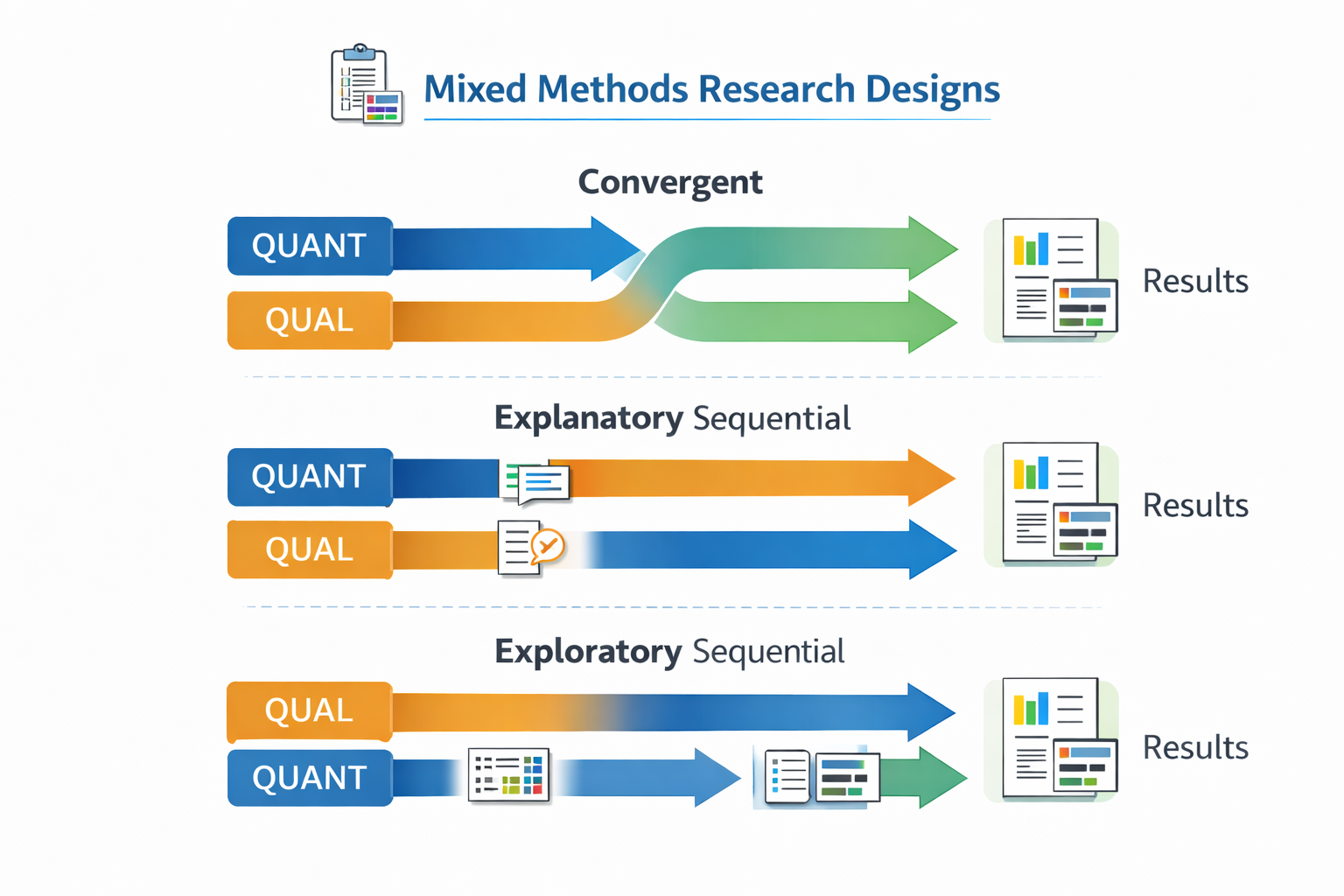

Examiners consistently penalise work that mixes assumptions without justification, such as using qualitative interviews to make statistical claims or applying quantitative validity criteria to interpretive studies. Methodological clarity is therefore a core assessment expectation.

Choosing the right approach for your assignment

The choice between quantitative and qualitative research should be driven by the nature of the research problem, not by perceived difficulty or familiarity. Quantitative approaches are appropriate when the goal is explanation, prediction, or measurement, while qualitative approaches are suited to exploration, understanding, and theory development.

Strong academic work explicitly justifies this choice, demonstrating awareness of alternative approaches and explaining why the selected method best serves the research aims.

Using comparison as part of methodological justification

In higher-level assignments, students are often expected to compare methodological options before defending their final choice. This comparative reasoning signals methodological literacy and strengthens examiner confidence in the research design.

Rather than presenting quantitative and qualitative research as opposites, strong theses position them as complementary traditions with distinct strengths and limitations.

Methodological clarity as an assessment advantage

Clear, well-reasoned methodological decisions reduce examiner uncertainty and streamline evaluation. When assessors can easily see how research questions, methods, and analysis align, they focus on the contribution rather than searching for coherence.

Understanding the academic logic behind quantitative and qualitative research is therefore not only a methodological skill but a strategic advantage in university assessment.

Comments