When students ask, “why my research paper rejected,” they often expect a single mistake—poor English, strict reviewers, or a tough journal. In reality, rejection usually reflects a pattern: the manuscript does not meet scholarly expectations for clarity, contribution, methodological fit, evidence quality, or compliance. Journals and university examiners screen for these issues quickly because they signal whether the work is credible, assessable, and worth further review.

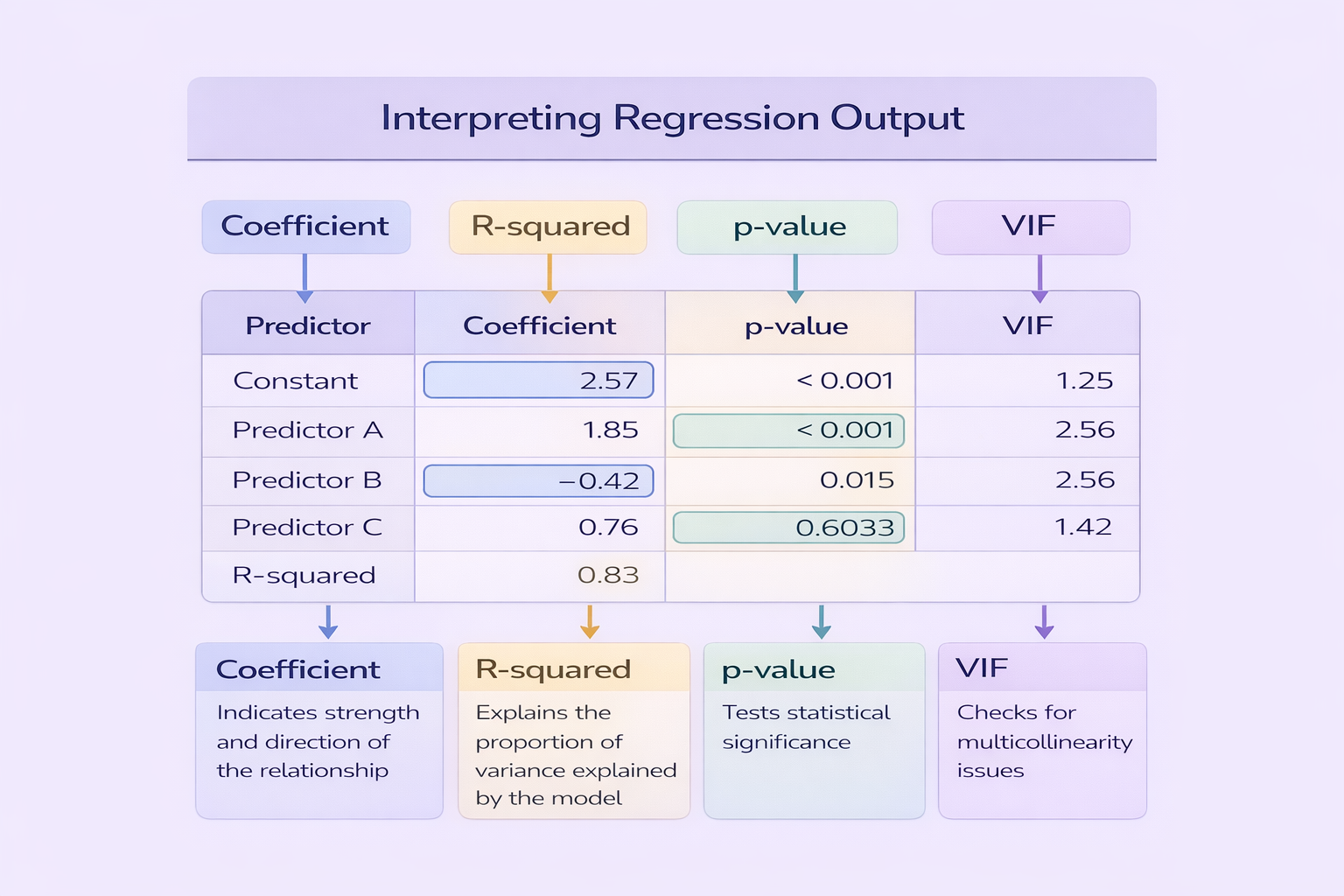

This guide expands the 12 reasons shown in the image—poor question, weak methods, insufficient literature, lack of novelty, inappropriate theory, flawed analysis, poor write-up, guideline non-compliance, unsupported results, ethical concerns, weak implications, and inadequate citations. For each, you will see why the problem exists academically, how it affects marking or peer review, and what typically goes wrong when students misunderstand the standard. Where relevant, you can strengthen related skills through Epic Essay resources on publishable research questions, methods vs methodology, causal inference, and final academic quality checks.

Most rejections are preventable: they arise from misalignment between the research question, method, evidence, and claims.

How editors and examiners decide: the rejection logic you must design for

Both journals and university markers work under time constraints and apply triage logic. They look for a clear research purpose, credible methods, transparent analysis, and a defensible contribution. If any of these are missing, they expect extensive reviewer effort to diagnose and repair the study, and that effort is rarely justified in competitive publishing environments.

For university research papers and dissertations, rejection equivalents appear as low marks or “revise and resubmit” decisions: unclear objectives, weak methodology sections, superficial analysis, and unsupported conclusions. The key insight is that these decisions are not primarily about style; they are about academic trust. Your manuscript must make its reasoning visible and verifiable.

1. Poor research question: unclear purpose and weak boundaries

A poor research question is the most fundamental reason a paper fails. Academically, the research question is the controlling logic of the entire manuscript: it determines what evidence is relevant, what methods are appropriate, and what claims can be made. When the question is vague or overly broad, the paper becomes descriptive rather than analytical, and the reader cannot judge whether the study succeeded.

What typically goes wrong is that students write “topic statements” instead of research questions. A topic (“social media and mental health”) is not a question. A question must specify population, context, variables or concepts, and the kind of relationship or meaning you are investigating. If your question lacks boundaries, your literature review becomes unfocused and your method cannot be justified. Use What Makes a Research Question Publishable? to refine specificity, feasibility, and contribution.

2. Poor methods: wrong design or weak justification

Methodological rejection occurs when your research design cannot credibly answer your research question. This includes inappropriate sampling, unclear measurement, weak operationalisation, and methods that are under-described or unjustified. Examiners treat this as a serious flaw because it undermines validity: even perfect writing cannot rescue a study that cannot produce trustworthy evidence.

A frequent student error is confusing “methods” with “methodology.” Listing tools (surveys, interviews, regression) is not the same as justifying why those tools fit the question and how they produce credible findings. Strong papers explain design choices, acknowledge limitations, and align claims to methodological constraints. If you need to correct your Methodology section language and structure, use Difference Between Research Methods and Research Methodology Explained for Students.

3. Insufficient literature review: weak scholarly positioning

An insufficient literature review signals that the paper is not intellectually situated in its field. Academically, the literature review does not exist to demonstrate that you can summarise sources. It exists to build a case for the study: what is known, what is contested, what is missing, and why your study is needed. When the literature review is shallow, outdated, or poorly synthesised, editors assume the study either repeats existing work or misunderstands the debate.

What typically goes wrong is “citation collecting” without synthesis. Students list studies sequentially rather than organising the review around themes, methods, contradictions, or theoretical debates. Another common failure is relying heavily on old sources while ignoring recent scholarship. If your paper lacks structural coherence across sections, the argument-building logic in Essay Structure Explained for University Students can help you reorganise the literature review as an argument rather than a catalogue.

4. Lack of novelty: no clear contribution

“Novelty” does not require a completely new topic. It requires a defensible contribution—new data, improved method, new interpretation, replication that changes confidence, or a context that challenges existing assumptions. Journals reject papers that resemble “what we already know” because publication space is limited and peer review time is costly. University markers similarly penalise research that feels derivative or purely descriptive.

Students often fail novelty by writing broad questions and producing predictable findings, then claiming contribution without demonstrating it. A robust novelty statement emerges from your literature review: it specifies the gap and explains how your work fills it. If you cannot write a precise contribution statement, your paper likely needs reframing. Use publishable question criteria and ensure your research design genuinely produces new insight.

5. Inappropriate or missing theory: weak explanatory power

Theoretical weakness is often misunderstood as “not enough citations.” In reality, theory is the framework that explains why your variables or concepts matter and how they relate. A paper may contain data and analysis but still fail if it cannot interpret results through a coherent conceptual lens. Reviewers reject such work because it looks like a report of observations rather than an academic explanation.

Common errors include using a theory as decoration (briefly mentioned but not applied), selecting a theory that does not match the research question, or failing to define key theoretical constructs clearly. A strong theory section operationalises the framework: it shapes the research question, informs the design, and structures interpretation in the discussion. Without that integration, your “findings” become isolated facts rather than contributions to knowledge.

6. Flawed data analysis: wrong technique, weak explanation, or assumption violations

Data analysis is rejected when it is inappropriate for the data, insufficiently explained, or presented without basic validity checks. In quantitative work, common issues include using statistical tests that violate assumptions, misinterpreting p-values, or treating correlation as causation. In qualitative work, common issues include superficial coding, unclear theme development, or extracting quotes without analytic reasoning.

Examiners and reviewers expect you to justify the analysis technique and demonstrate competence in interpretation. If your study uses statistics, strengthen your interpretive discipline using Understanding Statistics and Probability: From Data Description to Decision-Making. If your paper implies causal effects, ensure the design supports those claims; Understanding Causal Inference helps you avoid the most common overclaim that triggers rejection.

| Analysis problem | Why reviewers reject it | What to revise |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical test does not match the variable types or study design | Results are not interpretable as stated and may be invalid | Re-select the test based on data type and design, then justify assumptions and limitations |

| Correlation presented as causal impact | Claims exceed what the evidence can support | Rewrite claims to match design, or redesign analysis with credible causal identification |

| Qualitative themes are only topics with minimal interpretation | Findings appear descriptive and not analytically grounded | Define themes as patterned meanings, support them with extracts, and interpret through theory |

| Analysis steps are missing or unclear | Work is not verifiable or assessable | Write a transparent analysis pipeline and report decision rules and checks |

Table 1 clarifies a key academic principle: analysis must be both appropriate and explainable. If the reader cannot follow how results were produced, the paper becomes unreviewable.

7. Poor write-up: language and structure obstruct interpretation

Poor writing is not merely “grammar mistakes.” It is writing that prevents accurate interpretation of the research. This includes unclear definitions, inconsistent terminology, disorganised sections, and arguments that drift away from the research question. Journals may desk-reject such manuscripts because reviewers would spend too much time decoding the text. Universities penalise them because unclear writing signals unclear thinking.

The fix is not cosmetic proofreading alone. You need structural clarity: a controlled introduction, a coherent literature review, a defensible methods narrative, results aligned to objectives, and a discussion that interprets without overclaiming. Before submission, use Essay Writing Checklist for Academic Success to run a disciplined quality audit. For high-stakes work, language refinement and formatting support through Essay Editing Services can improve clarity without changing academic ownership.

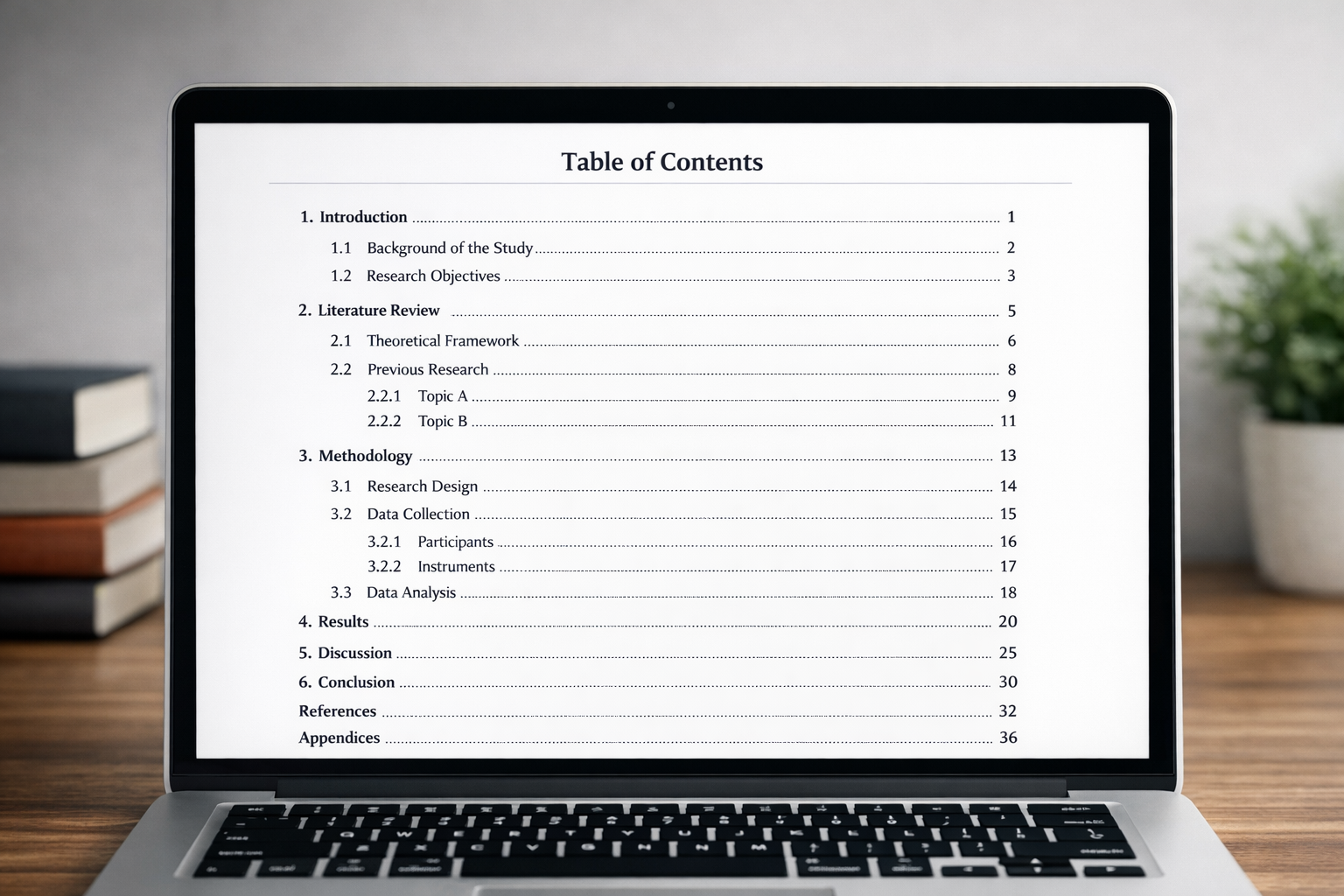

8. Journal guidelines ignored: formal non-compliance

Many authors underestimate how often manuscripts are rejected for technical non-compliance. Journals specify formatting, word limits, reference styles, figure requirements, disclosure statements, and reporting standards. Ignoring them signals carelessness and increases editorial workload. In competitive Q1–Q2 contexts, editors often treat non-compliance as sufficient reason to reject without review.

Students make a similar mistake in coursework by ignoring assignment briefs, required sections, or referencing style instructions. The academic fix is procedural discipline: build a submission checklist that includes all formatting and documentation requirements, and verify them line-by-line. If your paper includes appendices, ensure they are labelled, referenced in the text, and formatted correctly; Report With Appendices: Formatting Rules for Academic Submissions is a practical standard.

9. Unsupported results: conclusions not backed by evidence

Unsupported results occur when findings do not align with the research question or when the paper’s conclusions exceed what the data show. This often appears as sweeping generalisations from small samples, claims that ignore contradictory evidence, or discussions that introduce interpretations not grounded in the results section. Reviewers reject such work because it violates scholarly proportionality: claims must match evidence strength.

What typically goes wrong is that students treat the discussion as an opinion section. A strong discussion interprets results in relation to theory and literature, acknowledges limitations, and states implications cautiously. If you struggle to synthesise without repeating or overreaching, model the discipline of synthesis in How to Write a Conclusion Paragraph for University Essays and apply the same restraint to your journal-style discussion.

10. Ethical concerns: missing approvals, unclear consent, undisclosed conflicts

Ethical concerns trigger rapid rejection because they create reputational and legal risk. Journals and universities expect ethical compliance when research involves human participants, sensitive data, or potential harm. Problems include missing ethics approval where required, unclear informed consent, poor data anonymisation, and undisclosed conflicts of interest.

Even when ethics approval is not required, you must show ethical reasoning: how participants were protected, how data were handled, and how confidentiality was maintained. For journal-level norms, widely referenced standards include COPE and the ICMJE Recommendations. Using these frameworks does not guarantee acceptance, but it reduces risk and signals professionalism.

11. Poor implications: failure to explain “so what”

Poor implications occur when a paper reports findings but cannot explain why they matter for theory, method, or practice. This is a frequent weakness in student writing: results are described correctly, but the paper never clarifies what changes in knowledge or action because of them. Journals reject such manuscripts because readers require contribution, not only reporting.

Implications must be proportional to evidence. A small study can still have strong implications if it is framed carefully: it can identify a plausible mechanism, refine a concept, highlight a limitation in prior research, or propose an empirically grounded agenda for future work. If you want a structured way to state contribution types, use the logic in Dissertations & Research Papers guidance, which emphasises coherence between question, method, findings, and contribution claims.

12. Inadequate citations: weak evidence base and credibility signals

Inadequate citations include too few sources, outdated sources, irrelevant citations, and claims made without evidence. Journals interpret weak referencing as lack of field awareness; universities interpret it as poor scholarship and possible academic integrity risk. Referencing is not just a formatting requirement—it is the evidential infrastructure of academic argument.

Students often cite sources to “prove” common knowledge while failing to cite the claims that actually require evidence. Another common problem is relying heavily on non-scholarly websites where peer-reviewed sources are expected. Improve your citation discipline by ensuring every major claim is grounded in credible scholarship, and by integrating sources analytically rather than stacking quotes.

| Revision priority | What you should check | What a strong fix looks like |

|---|---|---|

| Research question and scope | Is the question specific, feasible, and aligned to the study design? | A narrowed question with clear variables/concepts, population/context, and a defensible gap statement |

| Methodology and transparency | Do methods match the question, and are procedures reported clearly? | A justified design, clear sampling and measurement, and an auditable analysis pipeline |

| Literature positioning | Does the review synthesise recent debates and justify novelty? | Themes or debates lead logically to a gap and show what the study adds |

| Claims and evidence alignment | Do conclusions exceed what the results support? | Claims rewritten to be proportional to evidence, with limitations made explicit |

| Compliance and presentation | Are journal/brief requirements met, and is the paper readable? | A submission checklist completed, references consistent, and structure coherent across sections |

Table 2 is designed for real revision work: start with the question and method, then strengthen positioning and evidence alignment, and only then polish presentation and compliance. This order prevents “perfect writing of a weak study.”

Quick tips to avoid rejection without turning your paper into a checklist

While the 12 reasons are useful, prevention requires a small number of high-impact habits. First, design your project so the question and method fit from the beginning. Second, position your study explicitly in current literature so novelty is visible. Third, treat methods and analysis as transparency exercises: write them so others can evaluate your choices. Fourth, discipline your claims so they never exceed your evidence. Finally, treat guidelines and referencing as academic integrity infrastructure, not administrative tasks.

- Use a question-quality test before drafting, such as the criteria in publishable research questions.

- Check analysis choices against assumptions and interpretation limits using statistics and probability guidance.

- Run a structured quality audit using an academic writing checklist.

These practices reduce rejection risk because they strengthen the paper’s underlying academic logic, not just its surface polish.

Why your research paper was rejected—and how to turn it into a stronger resubmission

Rejection is not a verdict on your intelligence; it is feedback about scholarly standards. The 12 reasons above are common because they reflect how academic knowledge is evaluated: clarity of purpose, credibility of method, strength of positioning, transparency of analysis, and proportionality of claims. When any one of these fails, the paper becomes risky to accept or hard to assess.

The strongest resubmissions do not merely “improve writing.” They redesign alignment: they sharpen the research question, justify method choices, rebuild the literature argument around a gap, correct analysis weaknesses, and rewrite conclusions to match evidence. If you treat revision as academic redesign rather than cosmetic editing, rejection becomes a practical step toward publishable work.

Comments