Choosing between thematic analysis vs content analysis is not a minor “methods” decision. It is a research design decision that shapes what counts as evidence, how you justify claims, and what examiners can reasonably expect you to conclude. Students often treat both approaches as interchangeable coding exercises, then lose marks because their analysis does not match their research question, their method description does not match what they actually did, or their results are presented in a form that their approach cannot support.

This guide explains thematic analysis and content analysis in an academically grounded way, aligned to typical university marking criteria: methodological fit, transparency, analytic depth, and defensible interpretation. It also clarifies when a mixed approach is legitimate and when it becomes methodologically confused. If you are still refining research design language, Difference Between Research Methods and Research Methodology Explained for Students provides a strong foundation for describing “what you did” and “why that approach fits.”

Why universities distinguish thematic analysis from content analysis

Universities distinguish these approaches because they produce different kinds of knowledge. Thematic analysis is typically used to develop and interpret patterns of meaning across qualitative data, such as interviews, focus groups, reflective diaries, or open-ended survey responses. Content analysis, by contrast, is often used to systematically describe and, in many versions, quantify features of content—such as how often particular categories appear in texts, media posts, policy documents, or transcripts. Both can involve coding, but coding is not the method; it is a technique within a method that has a specific logic of inference.

From an assessment perspective, the crucial issue is whether your interpretation is justified by the procedure you report. In thematic analysis, examiners look for interpretive depth, coherence of themes, and evidence that themes reflect a defensible reading of the dataset. In content analysis, examiners look for transparent category rules, reliability and consistency of coding decisions (especially if more than one coder is involved), and claims that match the level of analysis you actually conducted. When students misunderstand this, they produce “results” that are either ungrounded interpretation (in content analysis) or shallow counting (in thematic analysis), neither of which meets higher-band criteria.

A method is not defined by whether you coded. It is defined by what your coding is trying to establish: meaning patterns (thematic analysis) or systematic description of content categories (content analysis).

Thematic analysis: what it is, what it produces, and what it is best for

Thematic analysis is a flexible qualitative analytic approach used to identify, organise, and interpret patterns of meaning (“themes”) across a dataset. It is commonly applied when you want to understand how participants make sense of an experience, how identities and practices are constructed, or how a phenomenon is discussed across multiple accounts. In many university settings, thematic analysis is valued because it allows students to connect data extracts to conceptual claims, showing both evidence handling and analytical reasoning.

Academically, thematic analysis exists because qualitative research often needs a method for moving from raw data (words, narratives, descriptions) to defensible analytic claims. Themes are not simply “topics” that appear; they are patterned meanings that you argue for using a transparent analytic pathway. A well-executed thematic analysis typically includes: a clearly described coding process, a rationale for theme development, examples of coded extracts, and an explanation of how themes answer the research question.

What typically goes wrong is predictable. Students often mistake themes for headings (for example, “stress,” “time,” “motivation”) without explaining what those terms mean in the dataset and how they relate to a conceptual interpretation. Others create themes that are too broad to be analytic (“challenges students face”), or too close to the interview questions (“reasons for choosing the course”), which signals description rather than analysis. If your question is still broad, refine it using What Makes a Research Question Publishable? Key Criteria Explained, because thematic analysis becomes stronger when the question is precise about what kind of meaning you are investigating.

Content analysis: what it is, what it produces, and why it is often misunderstood

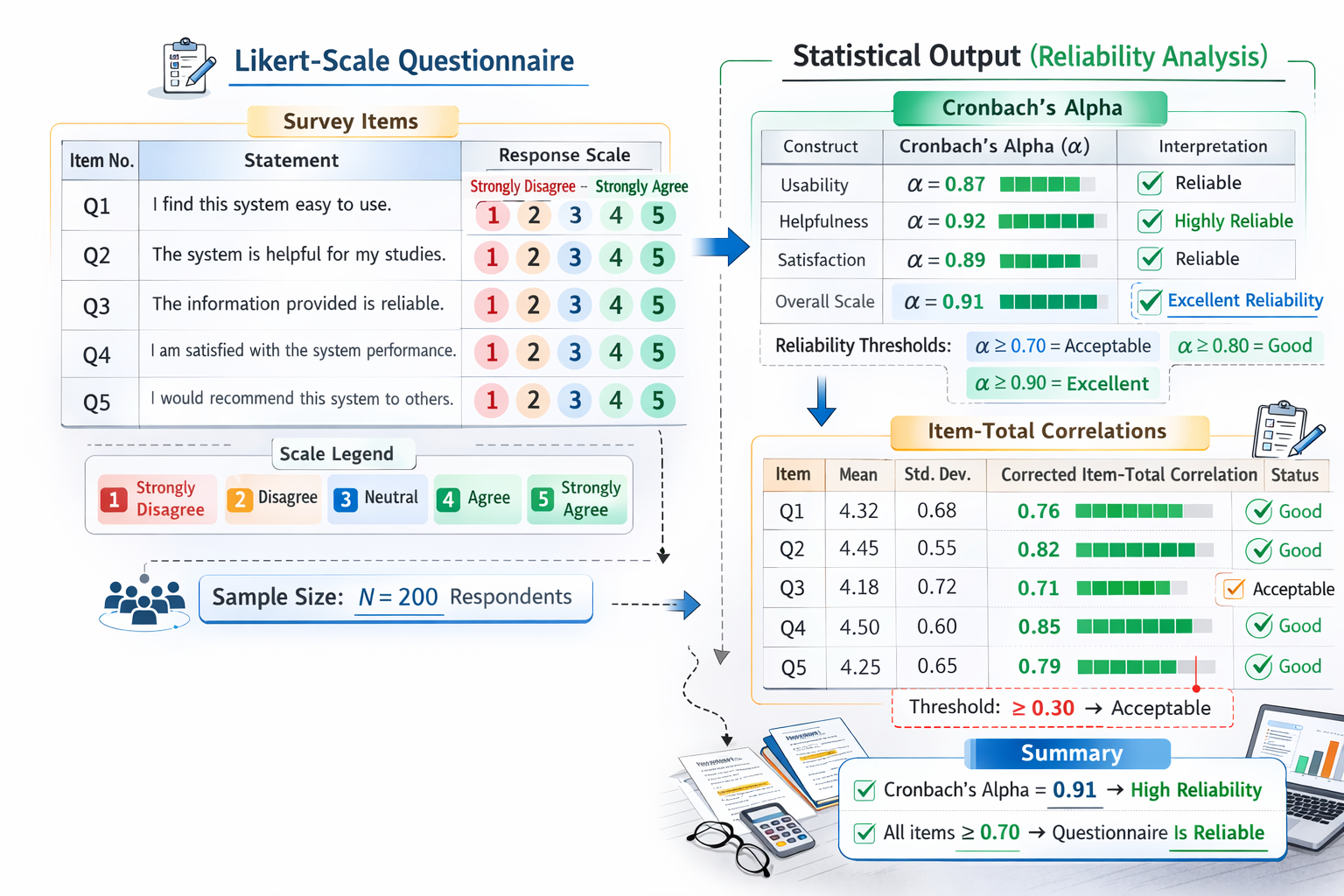

Content analysis is a systematic approach for categorising and describing content in a structured way. Depending on the tradition you use, it can be primarily qualitative (focused on structured interpretation of categories) or quantitative (focused on counting category frequencies and testing patterns). What distinguishes content analysis is its emphasis on explicit category rules: you define what counts as a category, how a unit of content is classified, and how coding decisions are applied consistently across the dataset. This is why content analysis is frequently used in media studies, communication research, policy analysis, and social science projects involving documents or large text corpora.

Academically, content analysis exists because researchers often need to make claims about patterns in texts that go beyond selective quoting. By applying a consistent coding scheme to many documents, you can justify statements such as “policy documents increasingly emphasise individual responsibility” or “news coverage frames migrants primarily through security language,” and you can support these claims with counts, proportions, or structured category summaries. Where content analysis is quantitative, the interpretation should be proportional to the evidence: frequency patterns can support descriptive claims, but they do not automatically support causal claims.

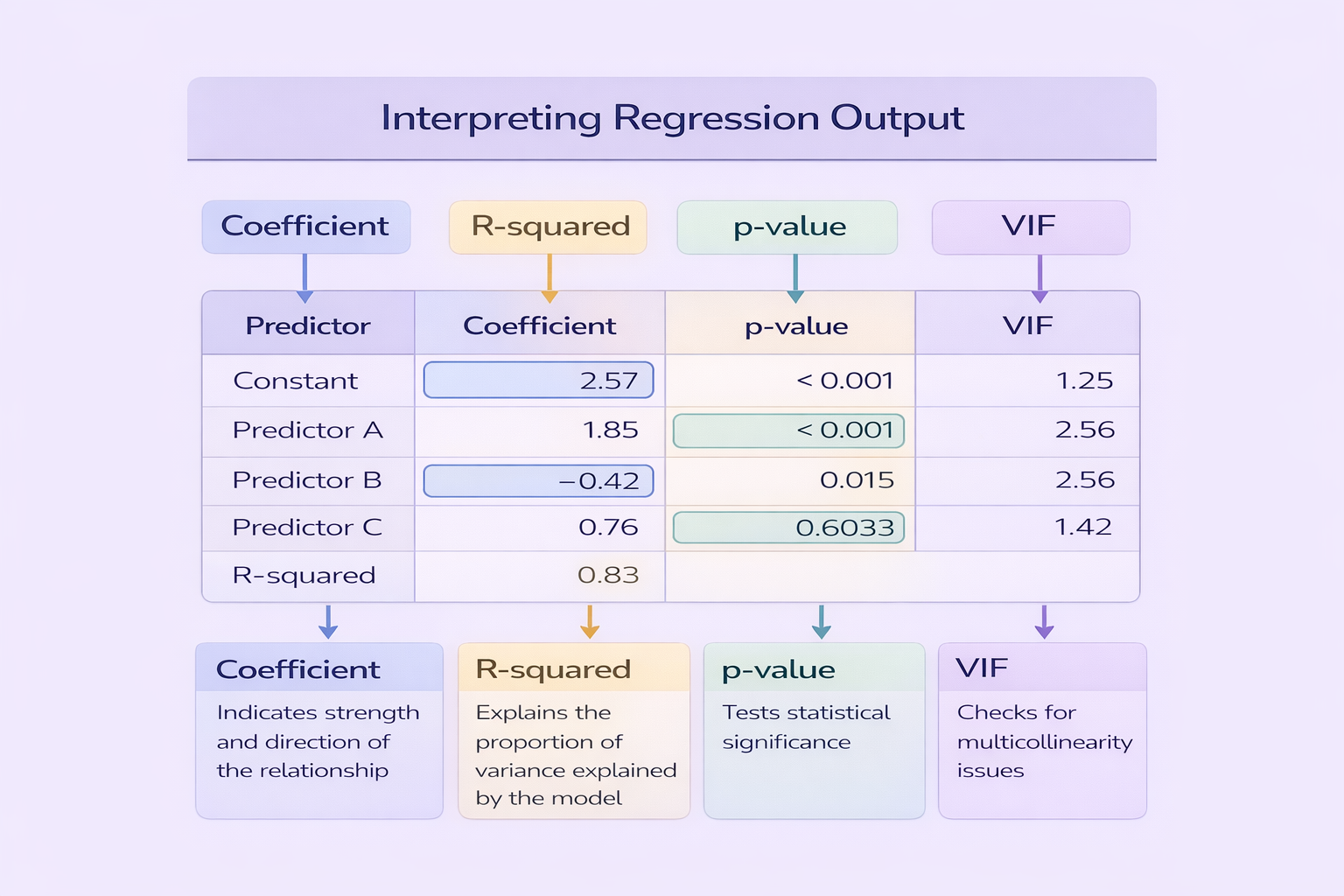

Students commonly fail content analysis by describing it as “I read the data and identified themes,” which is actually thematic analysis language. Others perform content analysis but report it as thematic analysis because they included some quotations. Examiners then penalise the mismatch. If your content analysis includes counts, proportions, or comparisons, make sure your statistical reasoning is credible; Understanding Statistics and Probability: From Data Description to Decision-Making helps you interpret numbers without overstating what they prove.

Thematic analysis vs content analysis in one examiner-friendly comparison

The image above presents an accessible contrast, but students still need an academically precise way to translate that contrast into a Methodology chapter. The table below provides a marking-aligned comparison that clarifies purpose, units of analysis, outputs, and common pitfalls.

| Dimension | Thematic analysis | Content analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary purpose | To interpret patterned meanings across qualitative data and develop themes that answer the research question | To systematically categorise content using explicit rules, often to describe or quantify patterns across texts |

| Typical data | Interviews, focus groups, reflective journals, open-ended responses, qualitative field notes | Documents, media posts, policy texts, transcripts, webpages, organisational communications |

| Unit of analysis | Meaningful segments of text interpreted in context; emphasis on meaning and concept development | Defined units such as words, phrases, sentences, posts, articles, or sections; emphasis on classification consistency |

| Typical outputs | Themes and sub-themes supported by extracts and analytic commentary that explains significance | Category frequencies, proportions, cross-tab summaries, or structured category narratives supported by coding rules |

| What examiners look for | Interpretive depth, coherent theme boundaries, evidence-to-claim reasoning, and reflexive transparency | Clear codebook rules, reliable coding logic, transparent sampling of texts, and claims proportional to evidence |

| Common student mistake | Reporting “themes” that are only topics, with little interpretation or weak linkage to the question | Using thematic language while actually doing frequency coding, or using counts to imply causality |

Table 1 also clarifies a key grading principle: examiners reward methodological congruence. Your question, your method description, your results format, and your claims must match.

How to choose the right approach based on your research question

The simplest way to choose between thematic analysis and content analysis is to ask what your research question demands as an answer. If your question begins with “how do participants experience,” “how do people make sense of,” “what meanings do students attach to,” or “how is identity negotiated,” you are usually seeking interpretive insights, not counts. Thematic analysis is typically the better fit because it provides a structured way to argue for meaning patterns across accounts.

If your question asks “how often,” “to what extent,” “what proportion,” “how frequently does X frame appear,” or “how do documents represent X across time or outlets,” you are usually seeking systematic description of content features. Content analysis is often the stronger choice because it allows a rule-based approach that can scale across many texts. If your project involves comparing groups, cohorts, or time periods, content analysis can also support clearer comparative claims—provided you do not imply causality without design justification. For students tempted to slide from patterns into causal claims, Understanding Causal Inference in Academic Research is essential for protecting academic credibility.

A step-by-step workflow for thematic analysis that meets marking criteria

A strong thematic analysis is not “read, code, theme, done.” It is an iterative reasoning process where you move between the dataset, your codes, emerging patterns, and your research question. Examiners expect to see a coherent analytic story: how your themes emerged, what they mean, and why they answer the question better than alternative interpretations. This does not require unnecessary jargon, but it does require transparent logic.

- Familiarisation with the dataset: Read transcripts or texts closely and note early patterns, contradictions, and emotionally or conceptually dense moments.

- Initial coding: Code meaningful segments with labels that capture what is happening, not just what the topic is.

- Theme development: Group related codes into candidate themes that represent patterned meanings across participants.

- Theme refinement: Check whether themes are distinct, internally coherent, and supported by multiple extracts rather than a single striking quote.

- Writing the analysis: Present themes as arguments supported by evidence, linking each theme explicitly to the research question and relevant literature.

The key quality marker is interpretation. A theme must do conceptual work, not merely label content. If you want to improve how your analysis is structured into readable academic sections, Essay Structure Explained for University Students can help you turn themes into coherent analytic sections rather than disconnected commentary.

A step-by-step workflow for content analysis that is transparent and defensible

Content analysis becomes academically credible when your categories are clear, your sampling decisions are justified, and your coding rules are explicit enough that another researcher could apply them. This is why content analysis is often linked to concepts like reliability and codebook design. Even if your assignment does not require formal inter-coder reliability, you should still show that your categories are applied consistently and that your conclusions are anchored in systematic evidence rather than selective examples.

- Define your dataset and sampling: Specify what texts you analysed, how they were chosen, and what time frame or boundaries apply.

- Define your unit of analysis: Clarify whether you coded words, phrases, sentences, sections, or whole documents.

- Build a coding scheme: Create categories with definitions and inclusion/exclusion rules; pilot the scheme on a small subset and refine.

- Apply coding systematically: Code the full dataset using the finalised rules, documenting exceptions and borderline cases.

- Analyse and report patterns: Present frequency patterns or structured category summaries, then interpret cautiously in relation to the research question.

When students include extensive supporting materials such as codebooks or coding examples, these often belong in appendices. To format these professionally and reference them correctly in the main text, use Report With Appendices: Formatting Rules for Academic Submissions.

When you can combine thematic and content analysis, and when you should not

In real research, it is possible to combine approaches, but the combination must be conceptually coherent. A common legitimate combination is to use content analysis to map the distribution of categories across a large dataset, then use thematic analysis to interpret how those categories operate in context. For example, you might quantify how frequently “risk framing” appears in policy documents, then use thematic analysis to interpret the meanings and assumptions within the most representative sections.

The combination becomes problematic when students mix logics without acknowledging it. A typical failure pattern is presenting counts (content analysis) but calling them themes (thematic analysis), then drawing interpretive conclusions without demonstrating how meaning was analysed. Another failure is using thematic analysis but including small, performative counts (“this theme appeared 12 times”) that do not strengthen interpretation and may mislead readers about the method. If you combine approaches, name them clearly, justify why both are needed, and ensure each output is used for an appropriate type of claim.

If your results are mostly frequencies and proportions, you are doing content analysis. If your results are mostly patterned meanings supported by extracts, you are doing thematic analysis.

What to write in your Methodology section so examiners trust your analysis

Methodology sections are often marked more strictly than students expect because they show whether you understand what makes your conclusions credible. Regardless of whether you use thematic analysis or content analysis, your methodology must explain: what data you analysed, how you sampled it, what your unit of analysis was, how you coded, how you developed categories or themes, and how you ensured your interpretation was disciplined. This is exactly the distinction explained in research methods vs research methodology: examiners want both operational description and conceptual justification.

Students often write methods sections that read like narratives (“I read the interviews and found themes”) rather than systematic accounts. A stronger approach is to use structured paragraphs where each paragraph states a methodological decision, explains why it fits the question, and clarifies what evidence it produces. If your dissertation or research paper is high-stakes, Dissertations & Research Papers outlines how research projects are structured and reviewed for academic coherence.

A practical decision tool you can cite in your assignment planning

The table below provides a decision tool you can use when planning a dissertation, research proposal, or coursework project. It is designed to prevent the most common mismatch: selecting an analysis method that cannot answer the question as asked.

| If your research aim is… | The better fit is usually… | Because the method can credibly produce… |

|---|---|---|

| To understand how participants experience a phenomenon and what meanings they attach to it | Thematic analysis | Interpretive themes that explain patterned meanings across accounts with evidence-based commentary |

| To map how texts frame an issue across many documents or media posts | Content analysis | Rule-based category patterns that can be described and compared systematically across a dataset |

| To compare representations over time, across outlets, or across groups | Content analysis (often with quantitative summaries) | Comparable category distributions that support cautious claims about shifts and differences |

| To interpret the underlying ideas, assumptions, or narratives embedded in accounts | Thematic analysis | Analytic interpretation that explains how meanings are constructed, not only that topics appear |

| To combine breadth (mapping patterns) with depth (interpreting meaning in context) | A clearly justified mixed approach | A systematic overview of content plus a defensible interpretive analysis of selected segments |

Table 2 also helps with writing your proposal. If you are still at the planning stage, Proposals & Coursework provides a practical view of how research planning decisions translate into assessed deliverables.

Credible external sources that support these definitions

When lecturers require research-led writing, it is useful to ground your method choice in foundational sources. Thematic analysis is widely associated with Braun and Clarke’s approach to developing themes in qualitative datasets. Content analysis is often associated with systematic category-based approaches, including qualitative content analysis frameworks and quantitative traditions used in communication research. The links below are credible starting points that you can cite in your proposal or methodology:

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology.

- Krippendorff, K. (Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology).

- Hsieh, H.-F. & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis.

Thematic analysis vs content analysis: how to finish with an academically defensible choice

Thematic analysis and content analysis are both legitimate, widely used approaches, but they are not interchangeable. Thematic analysis is strongest when your aim is to interpret patterned meaning and build conceptually rich themes from qualitative data. Content analysis is strongest when your aim is to systematically categorise content and describe or quantify patterns across texts in a transparent, rule-based way. Examiners reward the approach that fits the question, is reported clearly, and supports claims that are proportional to the evidence produced.

To choose well, begin with the question, not the software or the coding habit. Then write your methodology as an argument for credibility: explain what your approach allows you to claim, what it does not allow you to claim, and how you ensured transparency in your procedure. That combination—fit, clarity, and disciplined interpretation—is what consistently produces higher-band research writing.

Comments